From the late-1970s, the Goodfellow Unit emphasised meeting the needs of GPs and making continuing education interesting and accessible. By the end of 1979, which marked one year since he had commenced his position as the Director, Phil Barham had hosted over ten evening courses, four sessions on the role of physiotherapy in general practice, and one full day course on alcohol management.1 These lecture-style courses followed a similar format to the other short courses each regional Postgraduate Society organised around New Zealand at that time.

Short courses initially took the form of lectures

Yet many of those who participated in oral history interviews for this project remembered Barham’s determination to shift the short courses away from didactic teaching and towards more interactive learning. Dr Barham had reported his concerns with instructor-centred lectures during a session on ‘teaching in the practice’ at the Annual Medical Education Seminar of the Postgraduate Medical Committee at the University of Auckland in November 1975. He recounted conversations with house surgeons who had taken a full ‘two years to unlearn the passive student role with which they had become indoctrinated in undergraduate teaching’.2 Instead, he encouraged part-time staff and volunteers to develop lessons that focused on encouraging active learner participation. This included organising sessions on improving attendees’ practical skills, problem-solving, and engaging attendees in small group discussions.

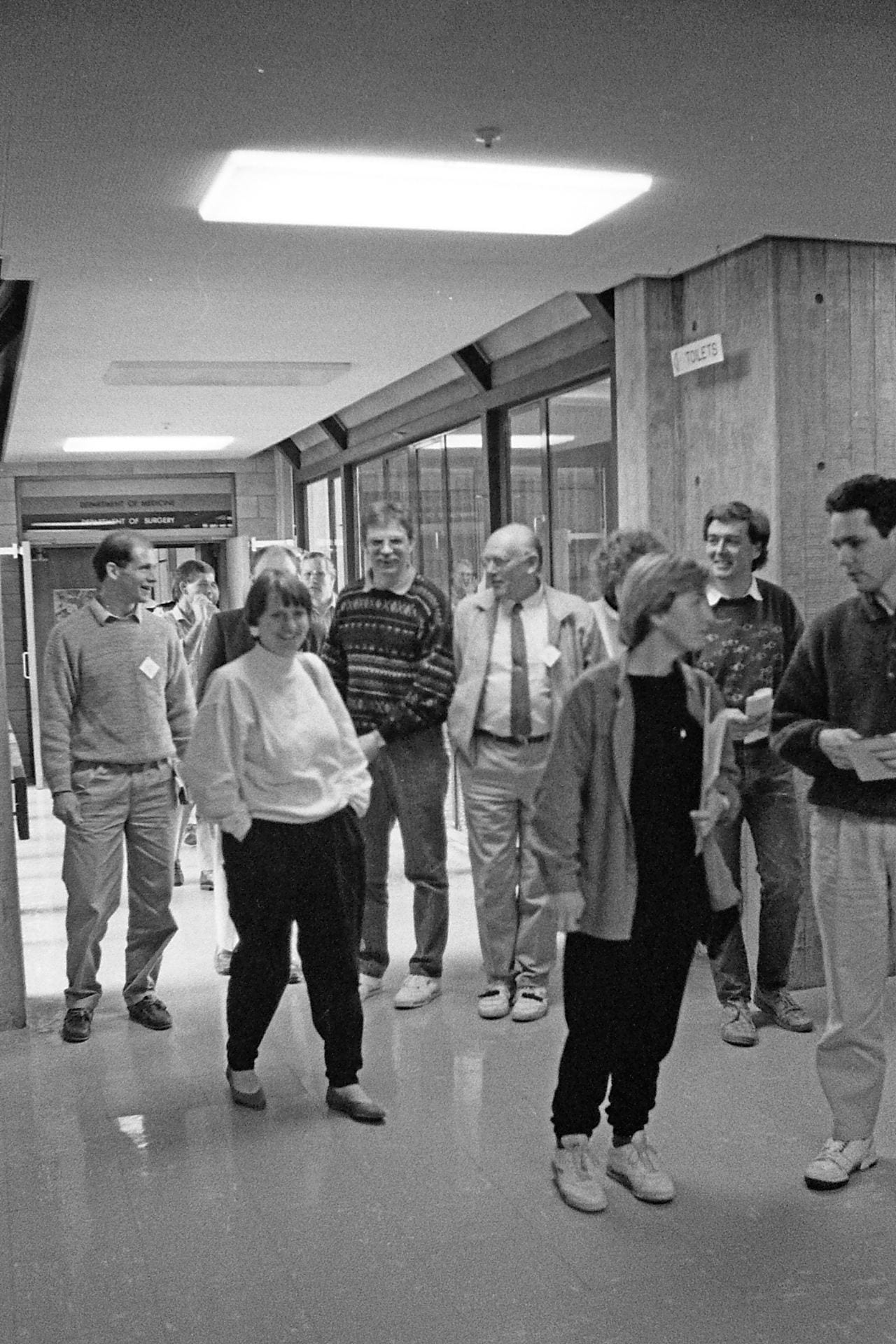

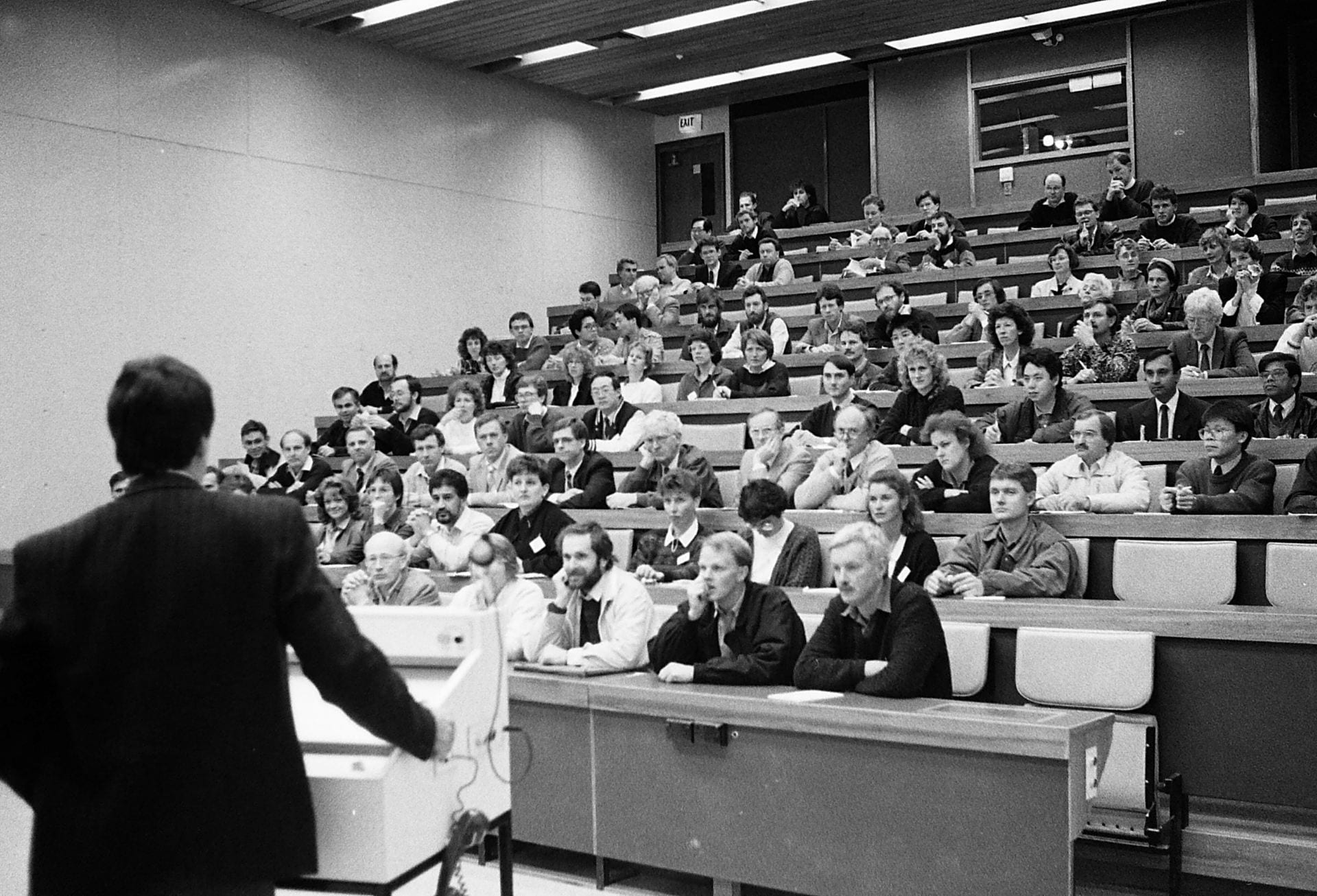

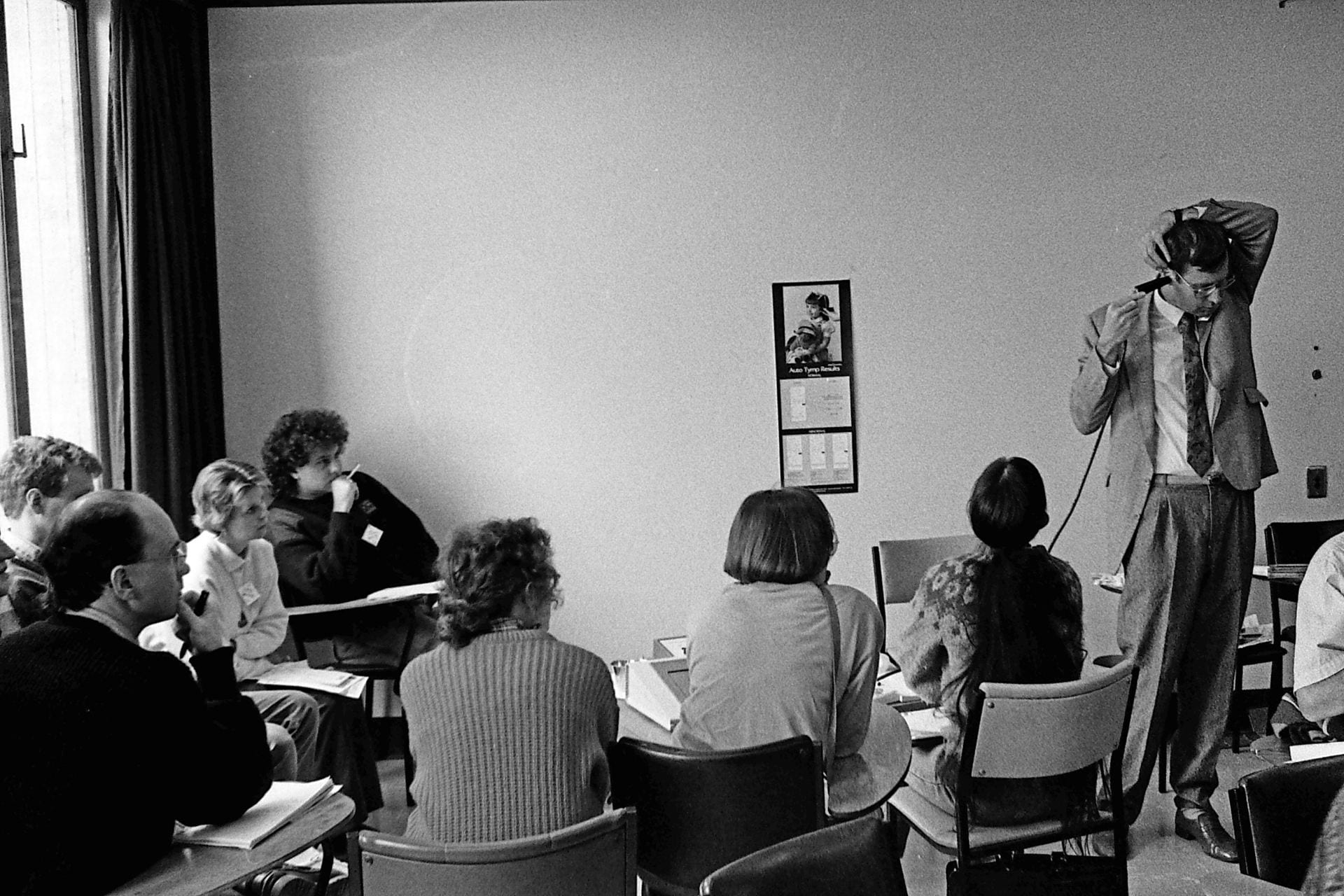

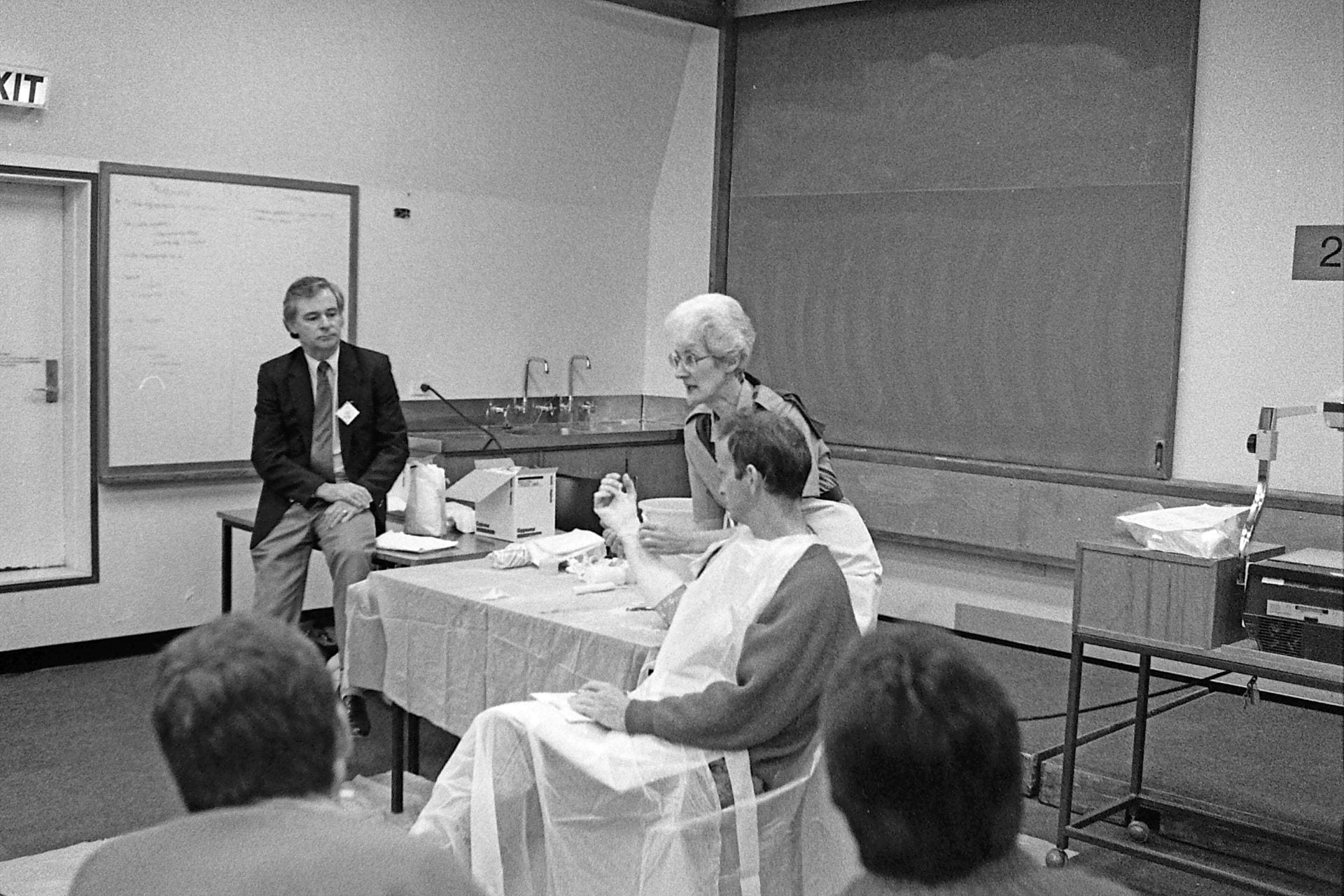

Short courses involved practical sessions whereby attendees practised new techniques on their peers. Images taken during a weekend course on clinical procedures, c. 1989.

The two-hour evening sessions or full-day weekend workshops proved to be popular among GPs. In 1982, Phil Barham reported that ‘almost despite ourselves [the courses] continue to increase in number, size, and range of topics’, and more than one third of GPs across the North Island attended at least one of the courses that the Goodfellow Unit organised in Auckland.3

In addition to emphasising peer-interaction during the sessions, Phil Barham and other staff aimed to ensure GPs had an active role in designing the courses and selecting topics that were of immediate relevance to their everyday practice. Campbell Maclaurin explained:

The tendency previously had been rather didactic teaching by specialists about their favourite areas of where they thought GPs failed, and Phil turned that around. […] All the activities were run by GPs and that was very different from having a physician or a paediatrician telling the GP what they needed to know, so much as the GP saying, ‘now this group of us here know damn well where there are gaps and we’ll recruit specialists as necessary to come and assist with it’. And they did. And it worked very well.4

Campbell Maclaurin on Phil Barham's teaching style

Changing these sessions to focus on the specific needs of GPs required the organisers to allocate topics and assert time limits on the invited speakers. Jocelyn Tracey became the Deputy Director of the Goodfellow Unit in the early-1990s. She explained that the Goodfellow Unit staff received a lot of support from other GPs who volunteered their time to organise two-hour evening courses or weekend sessions to ensure the programmes focused on the needs of GPs. Jocelyn organised role-play sessions with GPs to practise negotiating with specialists they invited to present at the sessions:

We would do role-plays about how to interact with specialists. So if you ring up an orthopaedic surgeon and say, ‘we’re planning to do something about arthritis’, and the orthopaedic surgeon says, ‘Oh, I’ve just been off to a conference and I know the very latest type of hip replacement that you should be doing and what prosthesis you should be using’, our eyes would glaze over and we would say, ‘Well actually, that’s probably not what the GPs need to learn about. We would really like to know about arthritis and this and this: Would you be able to speak about that?’ And the specialist would say, ‘Well, that would take me at least two hours’. And then we’d say, ‘Well I’m sorry, you’ve only got fifteen minutes and then we want some problems to discuss based on your talk’. So that was the beginning of changing it from didactic ‘the specialist knows best’ to what the GPs really need to know and how to best learn.5

Jocelyn Tracey on planning short courses

Many people shared fond memories of organising and participating in the Goodfellow Unit short courses that took place from the late-1970s to the early-2000s

Bruce Adlam also attested to the importance of engaging with specialists solely ‘as a resource person’ and rather drawing on the ‘knowledge that’s in the room’. Bruce had been part of the second intake into the University of Auckland School of Medicine in 1969 and had worked as a GP in the Bay of Plenty and as a locum in various hospitals in the UK, before returning to New Zealand and working as a general practitioner in Howick, Auckland.

Bruce joined the Goodfellow Unit as a Course Facilitator in 1993 or 1994. By the early-1990s, Phil Barham had developed what he termed the ‘modified triadic method’ and hosted training sessions for course facilitators to encourage them to apply the method to their courses. Bruce Adlam described this as a ‘GP-ised’ version of the triadic method of teaching, which comprised the specialist, the course facilitator, and the other GPs who attended the courses. The modified triadic method involved GPs identifying their main questions, and then collectively working through the answers with guidance from the specialist.

Bruce Adlam on the Modified Triadic Method

This style of teaching marked a clear departure from the other courses GPs had previously attended. Bruce explained, ‘We’d all been used to basically sitting in a chair, being talked at, going home, forgetting about it or knowing that there is something probably that I should be changing here but I’m not quite sure what’. Alternatively, the modified triadic method meant the techniques and skills they learned during the sessions ‘went straight from that discussion to being incorporated into your daily practice’.6

Some specialists certainly welcomed their limited roles in the sessions. Bruce recalled that the courses ‘were always really highly rated’ by both GPs and specialists, the latter of whom ‘would come back and say ‘Oh I really learned a lot today from that course, I didn’t realise what was happening in the GP world’.7

John Wellingham concurred. John worked with the Goodfellow Unit from 1989 to 1999, first as a course facilitator and then as the Quality Assurance Director. He explained that these courses ‘brought specialists and general practice people, in my eyes, much closer together’.8

Drs Bruce Adlam, John Wellingham, and Marc Shaw

John Wellingham on attending the courses

In addition to providing attendees with medical updates, from the mid-1990s course facilitators also focused on helping GPs to refine their communication skills during consultations with patients. Adlam’s colleague, Dr Marc Shaw had experience writing and directing plays and was a key influence in introducing the use of role-plays to the sessions. They hired actors to adopt the persona of the ‘difficult teenager’ during simulated consultations with GPs who attended the Goodfellow Unit courses.

Bruce Adlam described the debrief session at the end of the role-play as the ‘most powerful part of that learning’:

It wasn’t necessarily how successful you were in terms of your interview technique, but it was actually listening to what those role players would say when they had to answer ‘How are you like this person?’ ‘How are you not like this person?’ And the third question was, ‘What would your wise words be to me as the GP?’ So those were all really interesting take-home messages. They would say little things like, ‘Oh you fidget, or you’re clicking your pen, or I can see you’re interested but you’re just not on the right wavelength’. So those kinds of things were actually really helpful.

Bruce Adlam on role plays

Attendees at the Goodfellow Unit short courses, c. 1989

The short courses not only offered attendees some of the first continuing medical education sessions that were designed by GPs for GPs, but they also offered attendees important opportunities to meet and engage with their peers. In 1981, Phil Barham and research assistant John Benseman reported that short courses were especially popular among GPs who had few opportunities to discuss medicine with colleagues. These included those who worked in solo practices and those geographically isolated from the main hospitals.9

Associate Professor Nikki Turner, currently Director of the Immunisation Advisory Centre (IMAC) and Associate Professor in the University of Auckland’s Division of General Practice and Primary Health Care, attested to the ‘collegiality and social engagement’ she experienced during the short courses she attended in the early-1990s. Nikki had started to attend the courses as a ‘very junior doctor’ who had recently returned to New Zealand after several years overseas. She described the short courses as a place ‘where I felt like I was securely getting the support and backup as a part time GP to be safe’. As a GP who had ‘been out of the country for quite a while, it was quite nice to re-engage. It gave you community networks and it gave you skills and knowledge and support.’10

The short courses offered attendees with important networking opportunities.

The short courses met an important need for GPs who wanted to develop their skills and to engage with their peers. The attendance fees also generated a small income for the Unit. In the early-1990s, the Goodfellow Unit charged attendees $22 for evening sessions, and $110 for members or $165 for non-members to attend the weekend sessions. Barham reportedly described the fees as ‘chicken-feed by international standards’.11 Nevertheless, the courses faced serious competition from the sessions pharmaceutical companies had organised that were free of charge and often included complimentary meals.

Many Goodfellow attendees praised the courses for operating independently from pharmaceutical companies and the biases they associated with such sponsored meetings. The risk of competition from other providers did not materialise in full until the early-2000s.

As Ross McCormick, the Director of the Goodfellow Unit from 1998 to 2008, explained, by the early-2000s ‘the short courses were starting to get into trouble, the numbers were dropping’. Primary Health Organisations across Auckland and beyond offered short courses free of charge, and ‘people were going off to them because they were free and we weren’t’.12

The geographical location of the Goodfellow Unit posed another barrier to attendance. In February 2004, the Goodfellow Unit relocated from Griffin House, where it had been based since 2000, to the University of Auckland’s Tamaki Campus. The shift offered the Unit with opportunities for growth and engagement with local businesses.13 Yet many potential course attendees preferred to attend sessions at their work places rather than travelling to the new campus.

Ross McCormick subsequently decided to discontinue the courses for twelve to eighteen months. While his decision to do so reduced the cost of the Unit, it ‘felt like a disaster’ to stop hosting them. He questioned, ‘How can we be the Goodfellow Unit if we aren’t running short courses?’14

Ross initially planned to re-establish the courses as they were ‘part of our core business’. Yet a timely phone call from Andrew Wong from Mercy Ascott and the subsequent establishment of the Goodfellow Symposiums offered the Unit with a viable alternative to re-establishing the courses. In this regard, ‘the Symposium saved us’.

- 1. Philip Barham, Annual Report of the Sir William Goodfellow Director of Continuing Medical Education in General Practice, 31 December 1979, 3. ↩

- 2. ‘Teaching in the Practice, Fish Bowl Session’, New Zealand Family Physician vol 3, no 3 (1976): 30. ↩

- 3. Philip Barham, Annual Report of the Sir William Goodfellow Director of Continuing Medical Education in General Practice, 31 December 1982. ↩

- 4. Interview with Campbell Maclaurin, 11 September 2018. ↩

- 5. Interview with Jocelyn Tracey, 31 October 2018. ↩

- 6. Interview with Bruce Adlam, 12 December 2018. ↩

- 7. Ibid. ↩

- 8. Interview with John Wellingham, 22 November 2018. ↩

- 9. Philip Barham and John Benseman, The General Medical Practitioner as a Lifelong Learner: Realities and Prospects. An Exploratory Study of Continuing Medical Education (CME) Among General Medical Practitioners in the University of Auckland Area (Auckland: Department of Postgraduate Affairs, University of Auckland, 1981), 74. ↩

- 10. Interview with Nikki Turner, 14 November 2018. ↩

- 11. Carmel Williams, ‘User Pays Marks the End of a Philanthropic Era’, New Zealand Doctor, 19 March 1992, 56. ↩

- 12. Interview with Ross McCormick, 2 November 2018. ↩

- 13. Ross McCormick, Report on Goodfellow Unit Strategic Planning Day, 22 May 2003. ↩

- 14. Interview with Ross McCormick. ↩