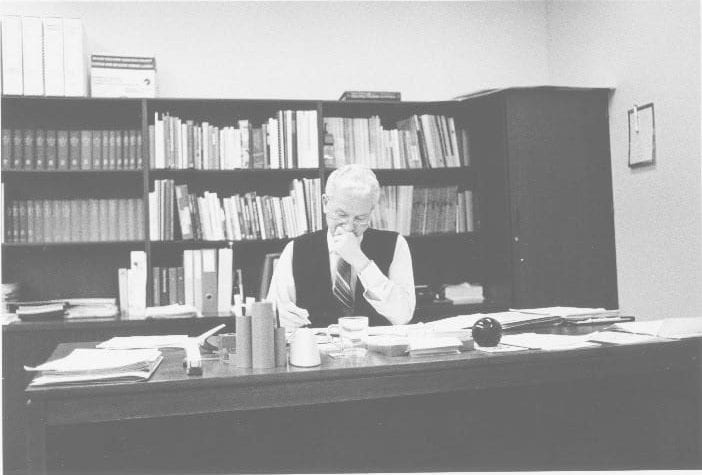

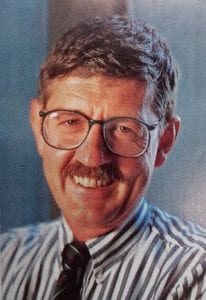

Dr Philip Middleton Barham, Director 1978-1998

Many of those who participated in oral history interviews for this project attribute the success of the Goodfellow Unit in its early years to the work of the inaugural Director, Dr Philip (Phil) Barham.

Current and former staff members cited Dr Barham’s approachability, emphasis on establishing personal connections with hundreds of GPs, and determination to create lessons that were of immediate relevance to the daily working lives of GPs as among the key reasons. Dr Campbell Maclaurin, who first proposed the appointment of a Director of continuing medical education, remained responsible for the Unit within his role as Associate Dean of Graduate Studies in Medicine. He described Barham as the ‘absolute heart of soul of what I was wanting to achieve’.[1]

Dr Phil Barham, 1928-2012.

Dr Barham was one of three medical practitioners who responded to the University Council’s advertisement for The Sir William Goodfellow Director of Continuing Medical Education in General Practice within the Department of Graduate Studies in February 1978.[2]

Phil Barham was born in Dannevirke in 1928. He completed his medical training at the University of Otago and later gained his Diploma of Obstetrics from the University of Auckland. Barham had gained considerable experience in delivering postgraduate education by the time he applied for the position as Director. He had served as the Chair of the Postgraduate Committee of the Faculty Board of the New Zealand College of GPs, conducted short courses in manual therapy for his colleagues in Dargaville, and had lectured for the St John Ambulance Service.[3]

Dr Barham had also pursued his own continuing medical education. Dr Brian McAvoy accompanied Barham from Dargaville to a training course at Whangarei Base Hospital in 1977. Dr McAvoy was visiting New Zealand on his return to Scotland from Canada. He described the hour-long drive from Dargaville to Whangarei as ‘an indication of the vastness of New Zealand’ and his astonishment that a ‘GP continuing his education would drive from Dargaville to Whangarei just for an evening meeting and then back again’.[4] Dr Barham’s pursuit of continuing medical education was especially noteworthy considering vocational training for GPs was just emerging at that time. There was even less sense of the need for continuing medical education among many medical graduates. Brian recalled it was almost a ‘rite of passage’ for medical graduates to burn all their textbooks because they had finished studying:

You were a doctor, you got your degree. That was one end of the spectrum. Some people really saw this as a process you had to go through for six years, but if you got your degree and you were a doctor then you could burn all your books. So there was no formal system of postgraduate training or continuing medical education.[5]

Dr Barham commenced his position in September 1978. He became responsible for continuing medical education for GPs in the Auckland, Northland, and Waikato Regions.[6] This included assessing the educational needs of GPs, organising workshops and refresher courses, and fostering connections with the Royal New Zealand College of GPs, the New Zealand Council for Postgraduate Medical Education, and the Department of Health, among other groups interested in further education.[7]

Yet as his role was the first of its kind in New Zealand, he noted there were ‘no precedents as to the nature of the job or its range of activity’.[8] Barham took the lead from others interested in continuing medical education for GPs, namely Drs John Richards, Rae West, and Campbell Maclaurin, and looked to overseas training centres for inspiration. He proposed undertaking an overseas study tour to observe international developments that could be adapted for the New Zealand context. Upon Maclaurin’s recommendation, the Education Committee granted Barham a six-week leave of absence to explore continuing medical education in Switzerland, the UK, Canada, and in the United States.[9]

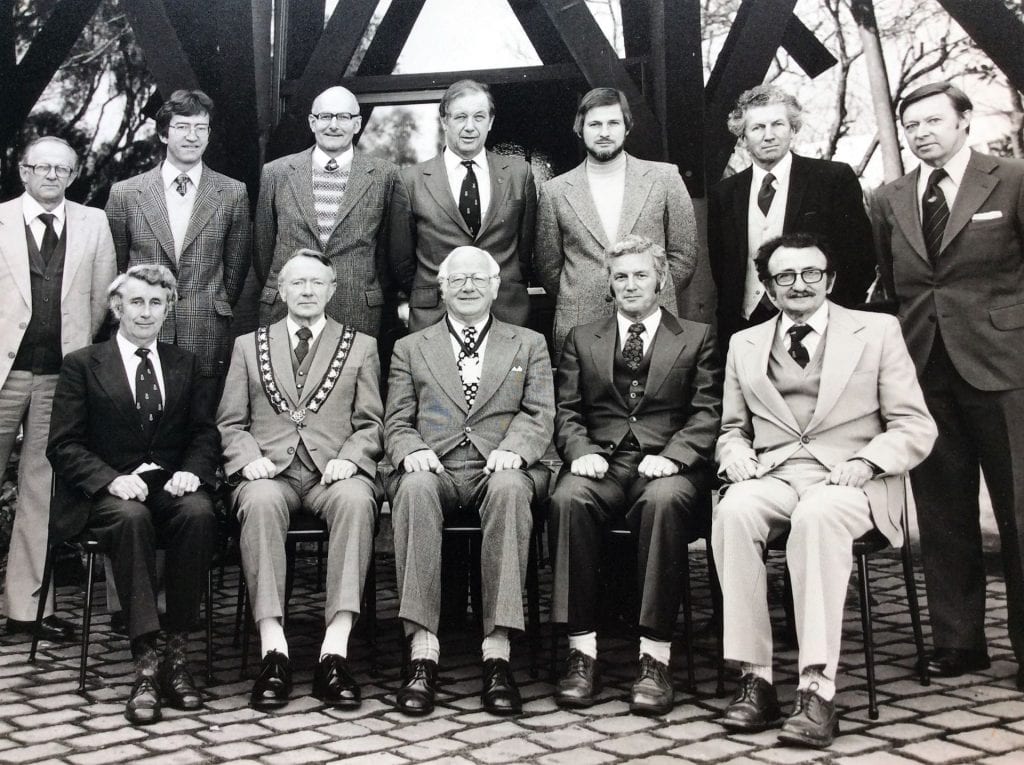

Dr Phil Barham (second from right, and front right beside Dr Rae West in 1981 or 1982) pictured with other members of The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners Council. Images supplied by West family.

Dr Barham was especially eager to learn about the continuing education needs of GPs in New Zealand. He observed that all prior efforts to gain insight into GPs’ perspectives required individual doctors to allocate time to completing and returning written questionnaires via post. Alternatively, he aimed to visit and establish personal connections with practising GPs to gain feedback about

their individual situations and to assess ‘the whole spectrum’ of their involvement in continuing medical education. By May 1979, eight months after he had commenced his appointment, Barham had personally visited four hundred GPs in the Auckland and Northland regions.[10]

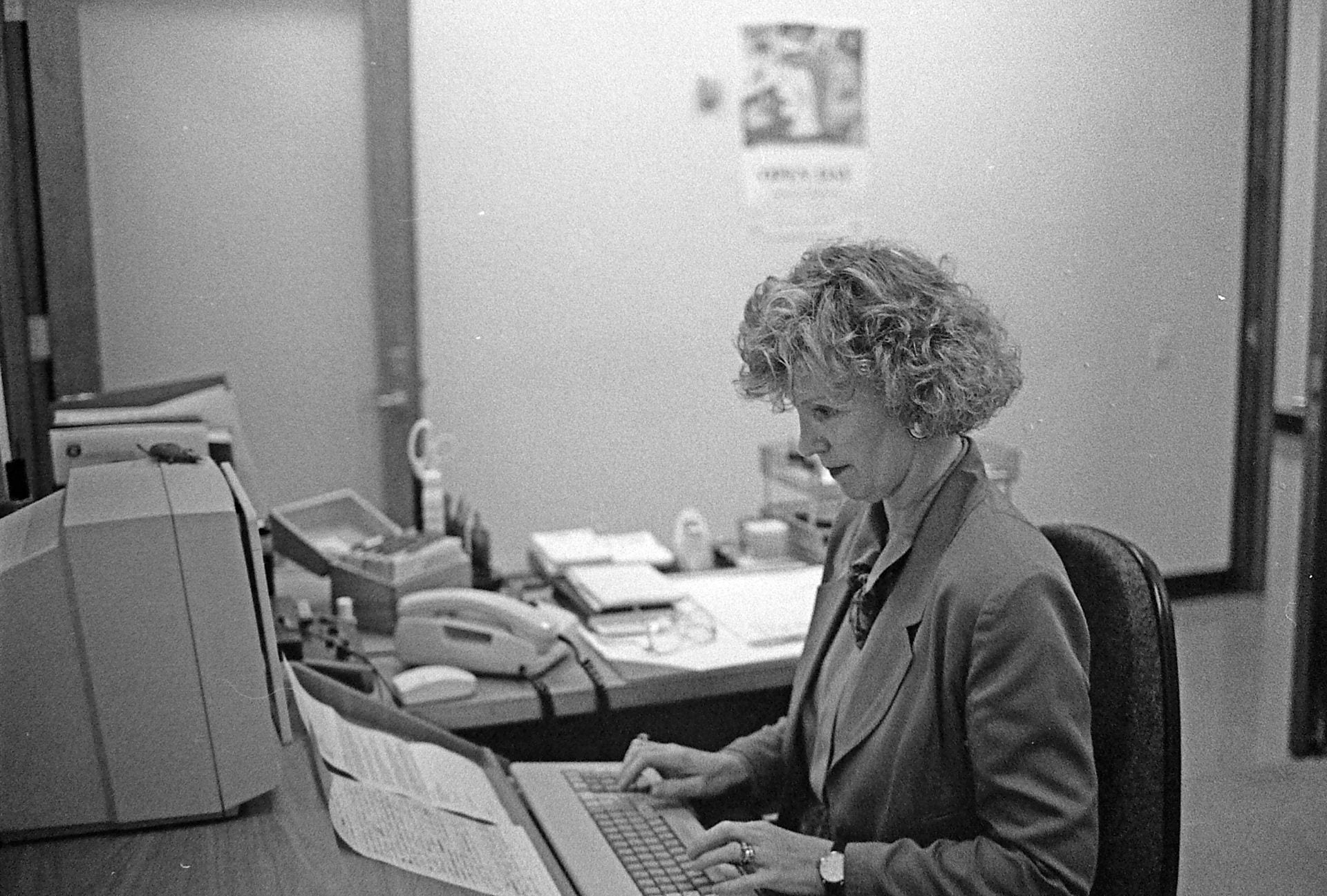

Many GPs were eager to learn more about the possibilities for continuing medical education. Yet some were considerably more skeptical about his objectives. Barham reported that ‘in a very few instances my reception has been cool but once they are convinced I am there to serve them not to criticise, then this reserve has always disappeared’.[11] The endowment from Douglas Goodfellow in 1977 also provided the salary for a secretary. In April 1980, Ina Hamilton became the first administrative assistant of the Goodfellow Unit.[12] GPs supported Barham’s and Hamilton’s endeavours by volunteering their time to contribute to developing, delivering, and attending the short courses.

Phil and Ina welcoming registrants at one of the short courses.

Across the early-1980s, Douglas Goodfellow also provided additional financial support for research officers. In August 1980, funding from the Sir William Goodfellow Trust and the Medical Education Trust enabled Barham to employ John Benseman to explore GPs’ perceptions of and engagement with continuing medical education.[13] Two years later in 1982, Douglas Goodfellow funded the appointment of Mary Hepple who took responsibility for managing distance learning.[14]

Phil Barham retired in 1998 after twenty years as the Director of the Goodfellow Unit. By that time, the Unit had grown to a staff of twenty-eight who offered a range of on-site and distance courses, individual and group workshops for quality improvement, and undertook external contract work. Douglas Goodfellow hosted a dinner in August 1998 to honour Dr Barham’s retirement.[15]

While Barham had initially planned to retire at the age of sixty-five in 1994, he agreed to remain in his position for another four years until the University appointed a replacement. Many expected Dr Jocelyn Tracey, the Assistant Director of the Goodfellow Unit, to take over Barham’s role. Yet the selection panel’s apparent refusal to offer Tracey a Professorship as was advertised, and rather the role of Director as an Associate Professor, disappointed many staff. Speaking with the New Zealand Doctor, one former staff member declared the Unit had ‘been taken over as a political football by the university’.[16] Eight of the twenty-eight staff of the Goodfellow Unit resigned in a matter of months.[17]

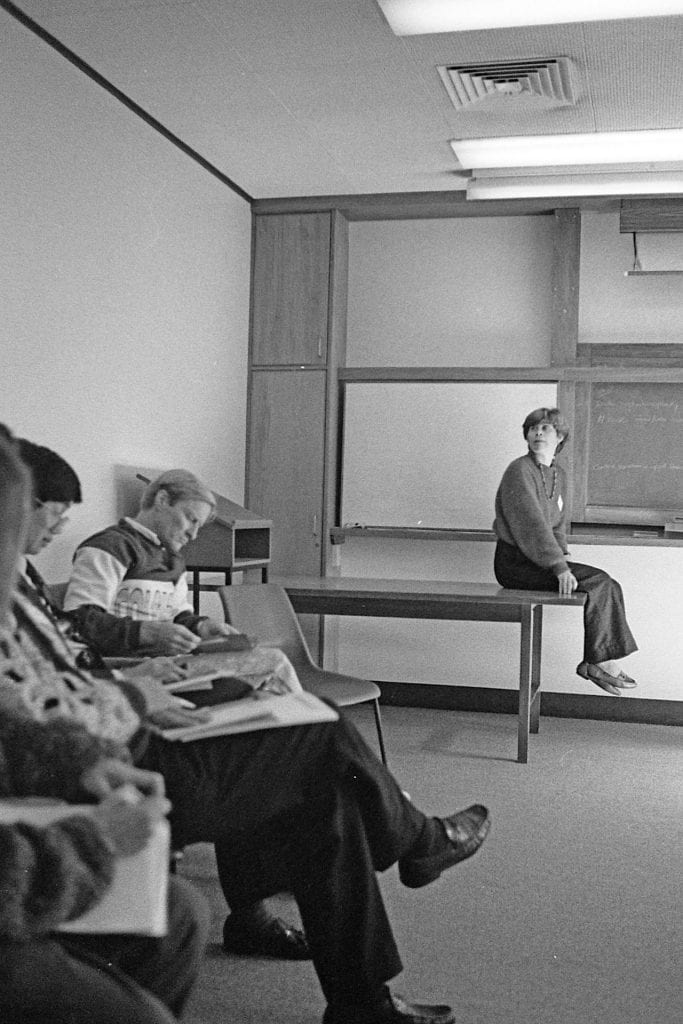

Dr Jocelyn Tracey, Assistant Director of the Goodfellow Unit early 1990s-1998

Jocelyn Tracey was part of the sixth cohort of Auckland Medical School in 1973.

Dr Jocelyn Tracey became the first Assistant Director of the Goodfellow Unit in the early-1990s. Jocelyn completed her medical training at the University of Auckland in November 1978 and worked as a house surgeon in Hamilton. She then spent eighteen months overseas and returned to New Zealand in 1985.

She became involved in delivering postgraduate medical education in 1986 when she saw an advertisement for a tutor in general practice with the Waikato branch of the Postgraduate Medical Society. While ‘older, respected male GPs’ usually ran the courses, ‘nobody wanted to do it’. The position appealed to Jocelyn and a friend who were ‘sick of doing our own housework and we figured out if we took this job we could each pay someone to do our housework and have much more fun doing this job. And it worked out really well.’ They were both ‘young and keen and interested, and we knew what was fresh and new to arrange the education around’.[18]

Jocelyn became involved with the Goodfellow Unit in late-1987 when she approached Phil Barham to supervise her MSc in medical science. Barham was ‘already known as the guru of continuing education for GPs’, and her colleagues from Hamilton often travelled to Auckland to attend the courses ‘because they were so good’. Barham had also undertaken postgraduate study in medical education in Sydney, and she felt he was ‘one of the few people in New Zealand who had real academic knowledge of postgraduate education’.[19]

Dr Tracey completed her MSc in 1989 and worked part-time with the Goodfellow Unit and part-time as a GP in West Auckland. She hoped to become the Director of the Goodfellow Unit once Barham retired and decided to pursue a PhD to help her to secure this position. In 1997, she became the first person in New Zealand to gain her PhD in the Department of General Practice at the University of Auckland, in which the Goodfellow Unit was situated.[20]

Jocelyn had also become the Assistant Director of the Goodfellow Unit by the time she undertook her PhD. She was initially responsible for working with other GPs to develop two-hour evening courses, or full day weekend courses. With the financial growth of the Unit and the increasing popularity of the courses across the mid-1990s, she also became responsible for liaising with representatives in the Waikato and Northland regions to deliver continuing education to other GPs in these areas, and helping to establish postgraduate diplomas in community medicine, sports medicine, and geriatric medicine.

Jocelyn facilitating a Goodfellow Unit short course and acting as an injured driver during a simulated car accident at the University of Auckland Open Day in 1996.

The flexibility and accommodation the Goodfellow Unit offered was especially important for Tracey and other staff members who were raising families:

If I had to come in for extra meetings, I just brought the kids with me. That was no problem. [Phil Barham] was really, really good with that kind of thing and really helped people. We couldn’t pay big wages because we were a university and so our idea was to try to make the job as family friendly as possible so there were other perks for people, which was great. And so you could choose your hours and do glide time as well. We had a number of solo parents working in the unit and we could adapt our hours to suit our family so it was really good.[21]

Jocelyn Tracey (second from right) with other members of the Department of General Practice including Ofa Nai, Gregor Coster, Nikki Turner, Dennis Kerins, Phil Barham, Bruce Adlam, and Ross McCormick.

Tracey left the Goodfellow Unit in 1998. She remembered the foundational years of the Unit as ‘ground-breaking. I think it changed the nature of education for GPs throughout New Zealand and it was certainly a very exciting, cutting edge place to work’.

Dr Tracey (front right) with current and former staff from the Goodfellow Unit at the 40th anniversary celebration in May 2018.

Dr Ross McCormick, Goodfellow Chair and Director 1998-2008

Ross McCormick joined the Goodfellow Unit as the Acting Director in 1998. Six months later, he became the inaugural Goodfellow Postgraduate Chair in General Practice and the second Director of the Goodfellow Unit. The Goodfellow Unit, the University of Auckland and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners had established the Goodfellow Postgraduate Chair in the first Memorandum of Agreement in August 1996. The appointed Chair also carried the Directorship and aimed to provide a strong academic base for staff. In the late-2000s, however, the growth of the Goodfellow Unit led the University of Auckland to divide the Chair and Director into two separate roles.

Ross McCormick did not initially plan to become a doctor. He had received a University National Scholarship after high school and completed a BSc in Chemistry and Mathematics in 1965 at the University of Auckland, followed by an MSc in Chemistry in 1966. He then pursued a PhD but realised, ‘I really didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in a laboratory’. It was a chance encounter with Professor Cecil Lewis, the first Dean of the Medical School, in 1968 that cemented his medical path. He recalled, ‘I said to him “if I was to apply for medicine would I get in?” and he said, “Oh yeah”. No Dean would ever say that these days.’[22] Ross started medical training in 1970 during the final year of his PhD.

Ross became involved with the Goodfellow Unit – which was the ‘only provider of short courses at that time’ – in 1979 when he started to work as a GP in Parnell. He described the courses as especially valuable for recent university graduates who had not yet gained membership of the RNZCGP. He attended the short courses as GPs ‘need to know something about everything and you need to be reasonably skilled at history taking and examination but also in knowing when to refer and when not to refer’.

Dr Ross McCormick (pictured in front of the window) attending one of the short courses.

The courses not only offered GPs with important opportunities for professional development but also created a chance for them to network and socialise with other attendees. He explained, ‘there were plenty of us and we’d all meet each other and have a chat and enjoy each other’s company, but we’d also hear some very good presentations often put on by GPs, but maybe put on by specialists with GP input’.

Ross McCormick on planning GFU sessions

Prior to joining the Goodfellow Unit, Ross McCormick had worked as an advisor to the area health board in 1989, and then as a medical director for primary care for the Regional Health Authority in the early-1990s until they were amalgamated under the Jim Bolger’s National government. He joined the University of Auckland as an Associate Professor in General Practice in the mid-1990s and was appointed as the Acting Director for the Goodfellow Unit in 1998. He became the Director six months later.

As Director, McCormick was closely involved in the Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs Project being run through the Unit, and had previously worked alongside Barham, Tracey, and clinical psychologist Peter Adams to develop the initial funding application for the project in the early-1990s. He had worked with drug and alcohol rehabilitation centres, conducted drug and alcohol assessments for regulatory bodies including the Air New Zealand Civil Aviation Authority and the Nursing Council, and was a Fellow of the Chapter of Addiction Medicine. The project aligned well with his expertise in drug and alcohol management. He also took responsibility for increasing the research output of the Unit and establishing the Goodfellow Symposiums.

Peter Huggard became the Assistant Director of the Goodfellow Unit in the mid-2000s. He described Ross McCormick as a ‘good person to work for. He said that Ross liked to push boundaries. I used to call him my “academic cowboy colleague” because he was willing to try things’.[23] Others also attested to the flexibility of the Goodfellow Unit in enabling them to launch new projects that might otherwise not have survived the University funding process. In this regard, Ross explained that Douglas Goodfellow’s ‘quiet backroom support and guidance’ was instrumental during his term as Director.[24] Douglas Goodfellow remained an active member of the Goodfellow Foundation until 2011, and ‘listen[ed] very carefully to suggestions on how to improve continuing education for GPs and then step in if there was trouble finding funding’.[25]

Dr McCormick left the Goodfellow Unit in 2008 when he was appointed to the role of Associate Dean Postgraduate at the University of Auckland. He reflected that the Goodfellow Unit had ‘very enthusiastic staff that are keen to ensure that general practice is well serviced and kept up to date’.[26]

Retiring in December 2014, Ross McCormick was made Emeritus Professor.

Dr Peter Huggard, Director 2008-2014

Dr Peter Huggard became the Deputy Director of the Goodfellow Unit in the mid-2000s, and then the Director in December 2008. Peter Huggard initially trained as a clinical chemist at Victoria University of Wellington. He then worked part-time in a sexual health clinic, as a volunteer with the St John Ambulance Service, and in Hutt Hospital from 1968 to 1980. Huggard had spent one year working in a children’s hospital in Toronto in the mid-1970s and returned to Toronto in 1980 when he was appointed as the chief technician of the hospital. He moved back to New Zealand five years later for a position managing laboratories in the National Women’s Hospital in Greenlane, Auckland. In 1992, Huggard completed a Master of Public Health followed by a Master of Counselling. He completed his Doctor of Education on the emotional impact of medical work on young hospital-based doctors in 2009.

Huggard became involved with the Goodfellow Unit in 2002 when was appointed to manage the postgraduate programmes within the Department of General Practice. He also taught postgraduate papers in therapeutic communication, loss and bereavement, palliative care, and contributed to the drug and alcohol training programme. Huggard has ‘loved working in the postgraduate teaching area because they’re all old people like me, and particularly people who have come back to education’. Huggard’s passion for postgraduate education grew from his personal experience of returning to university in 1991. He described postgraduate courses as ‘diplomas of second chance. That was my story’, and expressed his gratitude to Professor Robert Beaglehole, the Head of the Department of Community Health, who ‘gave me a second chance and got me directly into postgraduate without an undergraduate degree’ in public health. While it is now more common for students to be admitted into courses without undergraduate training in the same field, twenty-five years ago it was way less common, so he was wonderful, I owe him a lot’.[27]

Peter Huggard became responsible for organising the Goodfellow Unit Symposiums when he took over the role as Director in 2008. That year, the Symposium increased to 530 general practitioners, primary health care nurses, sponsors, and exhibitors who travelled from around Auckland, Northland, and the Waikato.[28] Organising a Symposium was a new experience for Peter. He remembered printing each speaker’s PowerPoint presentation and ‘putting them in a binder that probably never got looked at again. But we thought that was the thing to do’.[29]

As was the case with his predecessor Ross McCormick, Peter Huggard credited the support he received from Bruce Goodfellow and other members of the board of the Goodfellow Foundation when he sought to explore new ventures as the Director of the Unit. They were ‘really supportive of trying new territory, taking risks, and seeing where things could go’ and offered a ‘sounding board and they would they ask the right questions’ from a business perspective.[30]

Peter Huggard’s fixed-term appointment concluded in 2014 when he accepted a position within the Department of Social and Community Health.

Dr Felicity Goodyear-Smith, Goodfellow Chair 2010-present

Felicity Goodyear-Smith is the current Goodfellow Postgraduate Chair of General Practice and Primary Health Care.

Felicity Goodyear-Smith had wanted to become a doctor since she was eight years old. She pursued science in high school and as the only year-thirteen physics student at Westlake Girls’ High School, she had to ‘run up the road’ to attend physics classes at Westlake Boys’ High School. Among those in her class at the Boys’ High School was Bruce Arroll, the current Director of the Goodfellow Unit. In 1971, Goodyear-Smith became

part of the fourth intake of students enrolled at the University of Auckland’s School of Medicine.[31]

After several years working as a doctor overseas, Felicity returned to New Zealand and opened a practice in Freemans Bay in 1981. She established an informal peer group with other self-employed GPs who covered one another’s clinics and organised monthly dinners for their own continuing medical education sessions. They invited a specialist to each dinner to learn about ‘what GPs do badly’. She recalled the specialists ‘would say, “Oh, GPs don’t do anything badly”, and then they’d tell us all the things that they thought we should do better [laughs]. So that was our CME’.

Felicity Goodyear-Smith on the lack of CME before the Goodfellow Unit

Dr Goodyear-Smith joined the Goodfellow Unit on a part-time contract in 2000. She worked alongside Dennis Kerins, the Director of Educational Resource, to create online quizzes which were of educational value. She explained, ‘It didn’t matter if they got the wrong answer because basically after they’d answered it you would tell them what the right answer was and give the rationale, so even if they were wrong we would explain why’.

She also took responsibility for increasing the research output of the Goodfellow Unit by helping other staff to complete their analyses and writing for publication. Phil Barham had made research one of his final aims as the Director after what he identified as ‘some barren years of publishing’ within the Unit.[32] In 2000, Douglas Goodfellow established the Campbell Maclaurin and Philip Barham Research Fund, administered by the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, to support the Unit’s research output.[33] Yet increasing publications was a significant task. Dr Bruce Arroll explained that unlike most academics who trained in research, many Goodfellow Unit employees had been ‘taken out of general practice and put into a university and they slowly developed the skills of being academics’.[34]

Ross McCormick, the then Director of the Goodfellow Unit, appointed Felicity as a research facilitator. He explained ‘she would encourage people, and she would get people enthused, and she would say, “Oh, we can publish this by doing that”, and off it went’.[35]

Felicity was appointed as the Goodfellow Chair in 2010 and the Head of the Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care in 2013. She described the Goodfellow Unit as an ‘innovative initiative funded by the benevolence of the Goodfellow family’, which provides ‘very high quality continuing professional education for GPs and now for other primary health care practitioners in an environment initially where there was none’. She explained that the Unit also offers ‘a very top quality alternative to some of the education that may be available from drug companies which of course come with their own agenda. So, it’s always been focused on evidence-based and valuable material for practitioners’.[36]

Professor Bruce Arroll, Director 2014-present

Dr Bruce Arroll became the Director of the Goodfellow Unit in March 2014 following Dr Peter Huggard. Bruce initially planned to become an engineer after his high school principal advised him against undertaking a medical degree. He enrolled in a Bachelor of Engineering at the University of Auckland but transferred to medical school two years later in 1973.

Bruce Arroll became interested in medical education as an undergraduate student and served on the Medical Education Committee. In 1981, he accepted an offer to join the family medicine programme at McMaster University in Canada, whereby ‘evidence-based learning’ was starting to be applied. He recalled,

After returning to New Zealand in 1987, Bruce undertook a PhD in the Department of Community Health, supervised by Professor Robert Beaglehole. He joined the Department of General Practice as a Senior Lecturer in 1991 and shared offices with Rose Lightfoot and other staff from the Goodfellow Unit, ‘so we were always rubbing shoulders with each other’.We were taught how to read a medical journal article, which I wasn’t taught at medical school. When I came through, the senior – man usually, but occasionally a woman – would be right. Their opinion was right and no matter how much you knew you would always have to defer to them. And with evidence-based medicine you learned how to critique papers and you could know more about a topic than the boss, literally. It was very liberating in that sense.[37]

He also become more closely involved in the Goodfellow Unit’s short courses as both a course moderator and an attendee in order to ‘keep up my education’. He remembered the sessions that took place across the late-1980s and early-1990s as ‘very didactic in those days. It was usually a specialist talking at GPs, but I know Phil was trying to get away from that and get more GP involvement and so he did a lot of innovative things’.

Professor Arroll became the Director of the Goodfellow Unit in 2014, after having served as Head of the Department of General Practice. Professors Felicity Goodyear-Smith and Ngaire Kearse, who had been appointed as the Head of School of Population Health, approached Bruce to accept the position. While he ‘was curious’ about the position, he did not ‘didn’t leap at the idea to start with, because I guess I was still at the point of developing my academic career’. Yet he also saw the position as an opportunity to ‘put the evidence into practice’. He explained the ‘problem with academia is that we’re developing all this information, but no one is doing anything about it. So, let’s maybe start to implement some of the stuff and get the information out there in a way that people can digest’.[38] The idea of communicating new research to GPs in ways that they can apply almost immediately aligned with Douglas Goodfellow’s hopes when he founded the Unit in the late-1970s. Bruce decided to accept the position.

Under Bruce Arroll’s direction, the Goodfellow Unit has developed podcasts, webinars, fortnightly Goodfellow Gems which feature medical updates for GPs, and Red Whale, a single day course developed by the UK organisation Primary Care International that offers medical updates to primary health care providers onsite and online.

Bruce Arroll on Red Whale

Bruce Arroll has been especially involved in redesigning the Goodfellow Unit Symposiums to shift the focus away from research and towards information of immediate relevance to GPs with the theme ‘Skills for Monday’. Felicity Goodyear-Smith explained that he has ‘really taken the Goodfellow Unit to new heights with the Symposium, the webinars, and the podcasts. It’s always been a high-quality Unit in terms of the products it’s produced, but Bruce has made it particularly good.’[39]

Bruce Arroll final reflections

Bruce reflected on the Goodfellow Unit as one that ‘makes better primary care clinicians … which is what Douglas Goodfellow wanted’. Their engagement with technological developments including podcasts and webinars now means ‘you don’t have to go on a Tuesday night to the medical school anymore, you can be sitting at home with a glass of wine watching the kids run around and looking at a webinar, there are just all sorts of ways of getting this information’.[40]